Civil Rights Movement in Tampa: then and now

On April 4, 1968, Samuel Adams, a “Race Beat” reporter for the St. Petersburg Times, had the sad task of reporting on the death of a close personal friend. It was a friend that changed the face of America forever, a name that would not be soon forgotten, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Thousands gathered outside of familiar Hillsborough County landmarks, the streets were flooded with mourners. Outside of the Hillsborough County Courthouse in Tampa, a building that seems virtually unchanged through time, people of differing skin color, age, nationality, and religions held hands in silence as Dr. King’s life was remembered. From St. Petersburg to Daytona Beach, Floridians held hands in solace. As the crowd stood silently, with words of remembrance raining down on them, the idea of social justice echoed in the minds and hearts of many, including Adams who quietly took notes on the days happenings.

Much like Dr. King changed the face of Civil Rights, Adams changed the face of journalism. In a time when journalism was a white man’s career, and Civil Rights were quickly changing every day, Adams took a brave step and joined the St. Petersburg Times as a Race Beat Reporter. He had previously worked for the Atlanta Daily World, where he met Dr. King and debated the disservice being done to the black community by the press. Shortly after joining the St Petersburg Times, Newsweek magazine singled out the best reporters of the “most dangerous assignments in U.S. journalism” and one of those reporters was Adams, who bravely wrote a series called Highways to Hope.

Adams and his wife, Elenor, drove 4,300 miles through 12 Southern states to test compliance with the Civil Rights Act. The result was the series “Highways to Hope” that brought attention to the South that many people who were against Civil Rights feared would come to light. “The difficulty was that because hotels and motels were segregated, one would have to find places to stay. People always stayed with us in Waycross, so I had the resources to find places to stay to cover whatever it was. I traveled throughout the Southeast. I did fewer stories in Mississippi than in many places. I acknowledge I was selective. If I felt I couldn’t go in and come out with the story, then it was useless to go in,” said Adams in a recent interview.

“I remember when we would go to a motel, the black people and the white people couldn’t use the same bathroom, they couldn’t drink from the same fountain, and they couldn’t stay in the same type of room as a white person,” recalls Candis Bartlett, a resident of Tampa during the civil rights movement. “And that was just the late 60s. I can’t imagine how difficult it was before that.” “We didn’t really know how separated we were until we were much older,” recalls Evangeline Best, board member of the CDC of Tampa. “We were isolated, but that’s how our parents wanted us to be.”

The stories that Adams brought to the public of his journey through the South were filled with tales of heartbreak, anger, frustration, and a movement that would not be easily blown over. Adams found that, while it was a worthy goal, the “Social Justice” that his good friend Dr. King so desperately wanted, was not coming to fruition. When Dr. King passed, the idea of “Social Justice” was not lost, and journalists like Adams fought to keep it alive.

You may be asking yourself, “How does this have anything to do with me?”

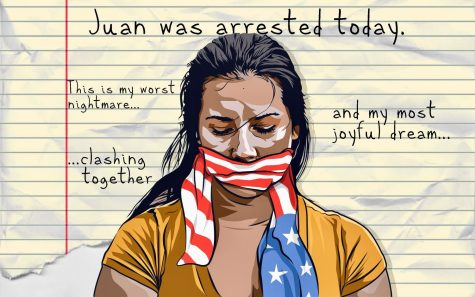

The civil rights movement is still alive, and social justice that Dr. King spoke of is a call for change. In the early 1960s, to Ms. Best, social justice meant protesting at a diner counter, being threatened by men with baseball bats, and risking her family’s livelihood when her father’s employer found out she was protesting. “To this day, I still will not sit in the back of the bus,” she proudly said. In the late 1960s, to Candis Bartlett, social justice meant donating her books to poorer people, helping to feed them and having food drives through her church.

In 2014, to HCC, social justice means bringing attention to the changes that still need to happen. Social justice means that everyone needs to pitch in to make their community a better and safer place to live. It means not judging people for face value, and realizing that inequality is still as alive today as it ever was and will be.

Krista Byrd is the Editor-In-Chief of The Hawkeye.

Krista Byrd was born in Brandon, Florida. She is currently working on her Associates degree in...

Marquise Tomlin • Mar 17, 2014 at 2:22 am

It’s good to see the preserverence that has come in the community. Often times it isn’t recognized. Many do not realize that we have a long way to go to get to peace. Tampa still is a very diverse city. Often we settle for borders in this city that separate race